Taxonomies have evolved over the years from being a way to navigate a website to providing the underpinnings of advanced ecommerce innovation. In the retail space many resources have been invested in creating the ideal user experience and presenting content and products that are appropriate for each user. The information they see is matched with their past purchases, needs, circumstances and behaviors. Leveraging ontologies and customer use cases can augment the power of taxonomies and provide an improved experience by translating insights about customer needs into information structures that directly serve those needs.

Evolution to digital for B2B

Manufacturers and distributors also need to provide a good customer experience, including offering products that are a match to their customers’ needs. At the heart of any sale, whether it is B2C or B2B, is the ability to provide answers to customers’ questions. In the retail world, there are many products, but the questions that buyers have about a particular product will be somewhat limited. Industrial products have many more possibilities because each product can have thousands of uses or applications. The products exist in combination with systems, components, tools, assemblies, and engineering designs that can be used in combination with hundreds or thousands of other items in products and solutions. Buyers have many questions and face numerous design challenges.

The B2B space has evolved more slowly than traditional ecommerce in part due to the complexity of the products and the associated buying process. Engineers needed trusted sources of information. The legacy model of large industrial catalogs that designers and engineers used as sources of reference and design ideas were considered their bibles. Manufacturers and distributors of industrial products published paper catalogs, which grew larger and larger as the offerings expanded.

These companies realized that the way to win business was to have the best information resources for their customers, which was typically in the form of a catalog. The catalog included detailed specifications and designs that helped engineers design their products and solve their challenging problems. In-house engineers collaborated with customers for “design wins” – ways for their products to become designed into the manufacturing process of the customer. In the case of big ticket or long-life products (especially in military and aerospace industries), a design win meant 20, 30 or more years of guaranteed sales for the life of the product.

Role of knowledge

B2B customers come to the site of a specialist manufacturer because that supplier has incorporated knowledge about solutions to problems into the engineering and manufacture of its products. However, surfacing that physical solution (knowledge embodied in a physical product) requires surfacing information about that solution from various perspectives. Users consider their problems in different contexts and have varying mental models to describe their needs. Are they looking for a particular item, say a wireless piezo sensor and actuator? Or are they looking for a solution for a remotely controlled device without a preconceived idea of the exact components? What type of input is required? Mechanical, optical, magnetic, thermal? If magnetic, is it inductive, or fluxgate? What kind of actuator? Pneumatic, hydraulic, or electric? Linear or rotary? And so on. Many factors can be relevant when a B2B customer is looking for a sophisticated product.

The questions that will lead users to solve that problem need to be represented by data on the manufacturer’s website – typically in a way that can be searched or queried as the user answers progressively more detailed questions about their needs. In the pre-Internet era, this was handled through a conversation, either in person or on the phone. Because it is difficult to capture all the knowledge for hundreds of thousands or millions of products with endless use cases, scenarios and details, many manufacturers of complex devices and components have depended more on expert interactions than on their websites. As the industry evolved, more of this information became readily available, but human experts are still part of the process, and B2B organizations are still challenged in developing the correct structures for accessing solutions.

Organizing a taxonomy

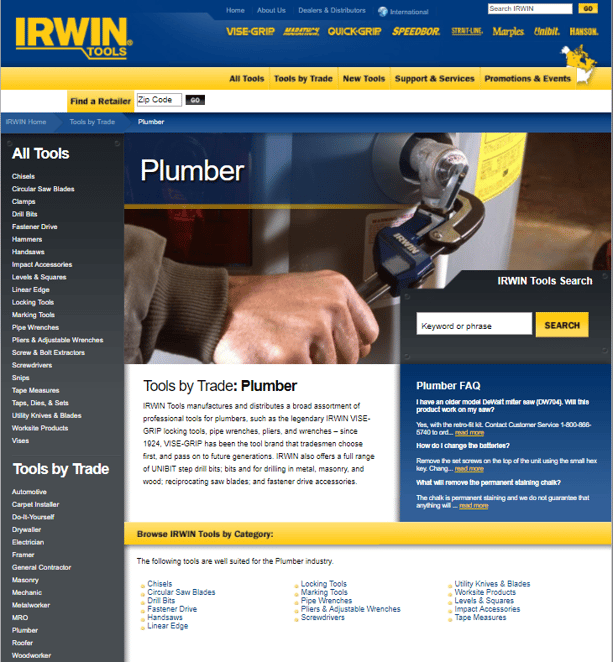

Taxonomies can be organized by “is-ness”– the fundamental nature of the object. For example, drills and saws are tools; plywood and 2x4s are different types of lumber. But they can also be organized according to “about-ness” –the characteristics of an object that would cause a buyer to choose one version over another, such as how much power they have (in the case of tools) or what type of wood they are made of (in the case of lumber). That is where the nuances of product details and attribute models come into play. A taxonomy can provide a broad grouping, but sub-groupings are created according to specific characteristics – such as the ones that describe actuator types.

Applications

Taxonomies can also describe applications of the product. What are the typical problems that they solve? This is where use cases are designed for audience and industry. An actuator for a laboratory application is very different from an actuator for an automotive application which in turn is vastly different than one used in the petrochemicals industry. There may be hundreds of thousands of use cases and problems to solve across all industries, but perhaps a few dozen when applied to a particular industry combined with an application. It is unlikely that a manufacturer of microelectronic mechanical actuators for lab equipment would also manufacture valve actuators for a chemical plant. Therefore, classifying products by application can be used to narrow the options to a more manageable number.

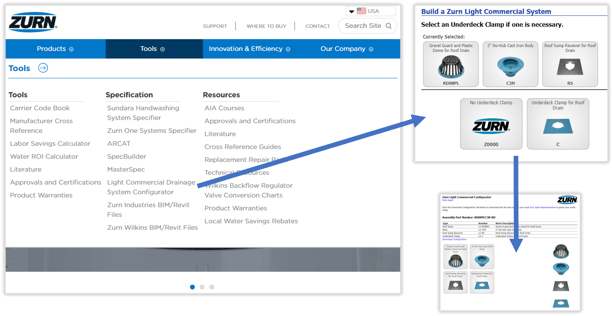

Solutions

Another way to describe products and product groupings is by solution. The distinction between applications and solutions can be insignificant in some industries and more meaningful in others. A solution addresses a particular need through a combination of products or products and services. That definition can also apply to an application. Certain products might improve safety, or be more cost effective. Others might have been designed to be more lightweight than previous versions of products, or energy efficient. Solutions can be considered from an engineering point of view, as a system of products, or they can be used to describe a more ambiguous requirement that has many different possible approaches. “Green” or “sustainable,” “energy efficient” or “extreme conditions.” Those terms can be descriptions of characteristics of products or a benefit achieved from using a product. Or even from a product application. These concepts can be subjective, context-dependent and based on common industry usage rather than being cleanly defined.

Taxonomies describe and codify expertise

Categories of applications and solutions are both context-dependent, and have different meanings depending on the nature of the industry and tools, systems, products, or components. Descriptive taxonomies, therefore, need to be developed specifically for each industry. The quality of the user experience is dependent not only on the quality of information but also on how well it is aligned with the user’s way of thinking about their problem. Solutions and applications taxonomies represent the expertise of the supplier, since they represent how that supplier organizes their product knowledge.

Choosing one supplier over another is partly determined by how well users can navigate and retrieve information to solve their problems and satisfy their need. Specialists know more about the unique technologies than the buyer typically does about their challenge. The buyer may not be aware of new ways of combining technologies and products that could save them money, increase reliability, improve safety, reduce turnaround time or offer other benefits to the ultimate customer. The unique competitive advantage of the organization is therefore dependent not just on their product selection and depth and quality of engineering and design, but also on how those differentiators are captured, codified, organized and represented through the user experience.

The implication is far reaching – your market value and the value in the mind of the customer – depends as much on your expertise as a knowledge engineer as it does on your expertise as a product design engineer in your area of specialization.

For more on this topic, check out this Earley Executive Roundtable: "Beyond Taxonomy - How Manufacturers & Distributors are Innovating in Ecommerce."